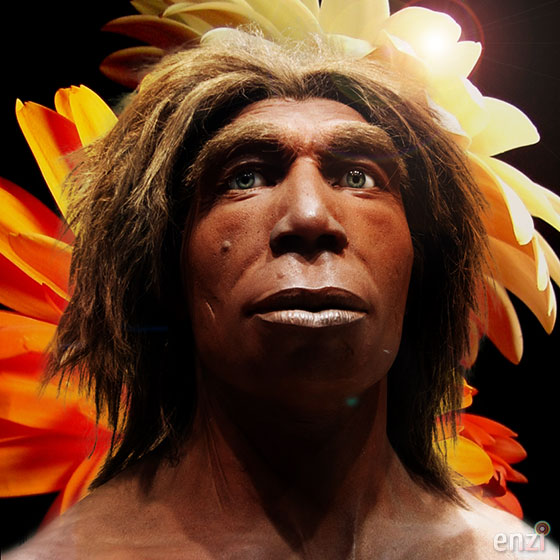

Homo neanderthalensis

Nicknamed Neanderthal, Homo neanderthalensis lived in Europe and southwestern to central Asia about 200,000 – 28,000 years ago. Neanderthals are our closest extinct human relative and it is estimated that about 5% of Europeans have Neanderthal DNA in them. Their bodies were shorter and stockier than ours, and they had a large middle part of the face, angled cheek bones, and a huge nose for humidifying and warming cold, dry air. These were all adaptations to living in cold environments. But their brains were just as large as ours and often larger – proportional to their brawnier bodies.

Homo neanderthalensis

Neanderthals made and used a diverse set of sophisticated tools, controlled fire, lived in shelters, made and wore clothing, were skilled hunters of large animals and also ate plant foods, and occasionally made symbolic or ornamental objects. There is evidence that Neanderthals deliberately buried their dead and occasionally even marked their graves with offerings, such as flowers. No other primates, and no earlier human species, had ever practiced this sophisticated and symbolic behavior.

Fossil and genetic evidence indicates that Neanderthals and modern humans (Homo sapiens) evolved from a common ancestor (likely Homo heidelbergensis who lived between 500,000 and 200,000 years ago). Neandertals and modern humans belong to the same genus (Homo) and inhabited the same geographic areas in Asia for 30,000–50,000 years; genetic evidence indicate while they may have interbred with non-African modern humans, they are separate branches of the human family tree (separate species).

Neanderthals and modern humans may have had little direct interaction for tens of thousands of years until during one very cold period when modern humans spread across Europe. Their presence may have prevented Neanderthals from expanding back into areas they once favored and served as a catalyst for the Neanderthal’s extinction. Over just a few thousand years after modern humans moved into Europe, Neanderthal numbers dwindled to the point of extinction. All traces of Neanderthals disappeared by about 28,000 years ago. The most recently dated Neanderthal fossils come from western Europe, which was likely where the last population of this early human species existed.

The first Neanderthal fossil was discovered in 1856 in Germany. In 1864, it became the first fossil hominin species to be named—geologist William King suggested the name Homo neanderthalensis. The fossils were found in the Feldhofer Cave of the Neander Valley in Germany (tal—a modern form of thal—means “valley” in German). Several years after Neanderthal 1 was discovered, scientists realized that prior fossil discoveries—in 1829 at Engis, Belgium, and in 1848 at Forbes Quarry, Gibraltar—were also Neanderthals. Even though they weren’t recognized at the time, these two earlier discoveries were actually the first early human fossils ever found.

Males averaged 5 ft 5 in (164 cm) and females 5 ft 1 in (155 cm) tall. Males averaged 143 lbs (65 kg) and females 119 lbs (54 kg) in weight.

During the winter of colder climates the number of plant foods Neanderthals could eat would have dropped significantly, forcing Neanderthals to exploit other food options like meat more heavily. There is evidence that Neanderthals were specialized seasonal hunters, eating animals whichever animalswere available at the time (i.e. reindeer in the winter and red deer in the summer). Sharp wooden spears and large numbers of big game animal remains hunted and butchered by Neanderthals have been found. There is also evidence from Gibraltar that when they lived in coastal areas, they exploited marine resources such as mollusks, seals, dolphins and fish. Chemical analyses of Neanderthal bones also tell scientists the average Neanderthal’s diet consisted of a lot of meat. Scientists have also found plaque on the remains of molar teeth containing starch grains—concrete evidence that Neandertals ate plants.

The Mousterian stone tool industry of Neanderthals is characterized by sophisticated flake tools that were detached from a prepared stone core. This innovative technique allowed flakes of predetermined shape to be removed and fashioned into tools from a single suitable stone. This technology differs from earlier ‘core tool’ traditions, such as the Acheulean tradition of Homo erectus. Acheulean tools worked from a suitable stone that was chipped down to tool form by the removal of flakes off the surface.

Neanderthals used tools for activities like hunting and sewing. Left-right arm asymmetry indicates that they hunted with thrusting (rather than throwing) spears that allowed them to kill large animals from a safe distance. Neanderthal bones have a high frequency of fractures, which (along with their distribution) are similar to injuries among professional rodeo riders who regularly interact with large, dangerous animals. Scientists have also recovered scrapers and awls (larger stone or bone versions of the sewing needle that modern humans use today) associated with animal bones at Neanderthal sites. A Neanderthal would probably have used a scraper to first clean the animal hide, and then used an awl to poke holes in it, and finally use strips of animal tissue to lace together a loose-fitting garment. Neanderthals were the first early humans to wear clothing, but it is only with modern humans that scientists find evidence of the manufacture and use of bone sewing needles to sew together tighter fitting clothing.

Neanderthals also controlled fire, lived in shelters, and occasionally made symbolic or ornamental objects. There is evidence that Neanderthals deliberately buried their dead and occasionally even marked their graves with offerings, such as flowers. No other primates, and no earlier human species, had ever practiced this sophisticated and symbolic behavior. This may be one of the reasons that the Neanderthal fossil record is so rich compared to some earlier human species; being buried greatly increases the chance of becoming a fossil!