Sirikwa people

Before the Maasai era, the Sirikwa had been the dominant population of the western highlands of Kenya. The Sirikwa region extended from Sotik in the south through Kericho, Nandi and Uasi Ngishu to the slopes of Mount Elgon and Cherangani hills in the north and to the North end of the Mau Hills and Nakuru in the east. They were prominent from 12th to 15th century.

The Sirikwa were primarily cattle herders, but they also carried out small scale cultivation and gathering of fruits and other wild plants.

A preserved Sirikwa site can be visited and observed at Hyrax Hill museum, Nakuru.

The Sirikwa disappeared as an ethnic group in the 17th and 18th century by amalgamating to new communities in the area, such as Maasai, Kikuyu and Kalenjins. Their language may have contributed to the Kalenjin languages. Sirikwa are also sometimes identified with the Oropom. The Sirikwa of Mau Hills and the Hyrax Hill near Nakuru, were assimilated into the newly emerging Maasai and other ethnicities of the 17th and 18th centuries thereby losing their Sirikwa identity. These Maasai ethnicities included the Keekonyokie section of the Maasai who before colonial appropriation of their land in 1905 occupied the Kinangop (Kinopop) area of the Nyandarua range adjacent to Murang’a, Othaya and Tetu areas of Nyeri and neighbouring Laipikia plains, formerly homes to Laikipiak (Wakuavi) Maasai. In these Agikuyu areas, the name Thirikwa (Sirikwa) is found as a male name indicating absorptions and assimilations of the Sirikwa people by the Kikuyu from the Maasai neighbouring communities in Nyandarua and Laikipia areas.

Although not ethnically closely related and despite different lifestyles, the Sirikwa had a close economical and cultural relationship with the hunter-gatherer tribe of Ogiek. They also shared linguistic similarities.

The Kony sub-group of the Kalenjin people according to their oral tradition extended from Mount Elgon and adjoining Western territory across the Uganda borders to Kapenguria and Kitale and they represent the remnants of the Sirikwa people. The Sengwer community living in the Cherangani Hills claim decendence from the Sirikwa, though assimilated to the Pokot since colonial times until the change of government in 2002.

Sirikwa were possibly linked to the Engaruka in Tanzania’s crater highlands and had relations with the Iraqw (Mbulu) people who still live nearby and speak a distinct South Cushitic language.

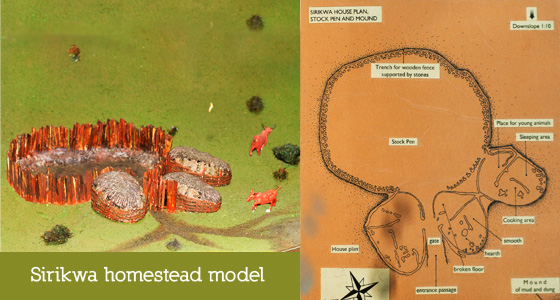

Sirikwa Holes

The Sirikwa culture is still evidenced by the Sirikwa Holes they left behind. These are round depressions having a diameter 10–20 metres and average depth of 2.4 metres and often built on hillsides. They were surrounded by stone walls or wooden fences. Sirikwa holes occur as clusters, with usually 5 to 50 holes at a site, but sometimes over one hundred. Nowadays these holes are often covered by grass and bushes.

One of several Sirikwa holes at Hyrax Hill, Nakuru.

The Sirikwa kept their cattle inside these fenced enclosures, but built their houses outside them. The holes and enclosures were built for defensive purposes. Sirikwa holes were semi-permanent, after several years they were abandoned and the communities moved to build new pens elsewhere.

Sirikwa territory ran from Lake Turkana in the north to Lake Eyasi in the South. Its cross-section ran from the eastern escarpment of the Great Rift Valley to foot of Mount Elgon. Some of the localities include Cherengany, Kapcherop, Sabwani, Sirende, Wehoya, Moi’s Bridge, Hyrax Hill, Lanet, Deloraine (Rongai), Tambach, Moiben, Soy, Turbo, Ainabkoi, Timboroa, Kabyoyon, Namgoi and Chemangel (Sotik).

The holes became inefficient due to increasing cattle raiding, particularly by the Galla and Borana and later the Maasai and Nandi. This forced the Sirikwa to disintegrate in various directions. Those who took the easterly route settled among the Kikuyu, Meru, Embu, Pokomo and even the Mijikenda in Shungwaya. Those who went down south founded such nationalities like the Kuria and Sonjo. Thimlich Ohinga on the south eastern shores of Lake Victoria is possibly a Sirikwa settlement. The group that went west via northern Mount Elgon ended up in the Kingdoms of Bunyoro, Buganda, Busoga. Others were ‘bantuized’ and went on to form the Abaluyia and Abagusii Bantu groups. The Babukusu sub nationality of the Abaluyia is supposedly 80 per cent Sirikwa.