- Home

- The Universe

- Human Origins

- The first ape men

- Proconsul

- Nakalipithecus

- Chororapithecus

- Sahelanthropus

- Orrorin Tugenensis

- Ardipithecus Kadabba

- Paranthropus aethiopicus

- Australopithecus Anamensis

- Ardipithecus Ramidus

- Australopithecus Afarensis

- Australopithecus Africanus

- Australopithecus sediba

- Paranthropus boisei

- Paranthropus robustus

- Kenyanthropus platyops

- Australopithecus garhi

- Stone age cultures & technologies

- Stone Age ancestors

- Out of Africa Migration

- The first ape men

- Civilisation

- Peoples & Cultures

- Interactive Exhibitions

- Museums of Kenya

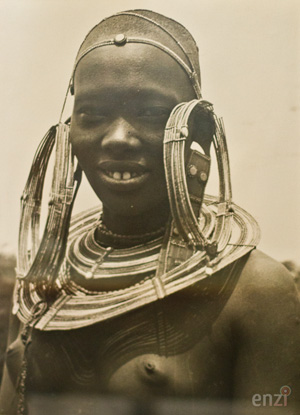

Plain Nilotes

Kenyan Plain Nilotes include the Maasai, Samburu, and Turkana, Teso, Njemps, Nubi – and have traditionally practiced nomadic pastoralism.

Language: Maasai. Alternate names: Masai

A Nilotic ethnic group of semi-nomadic people living in Kenya and northern Tanzania, the Maasai society is comprised of sixteen sections (known in Maasai as Iloshon): Ildamat, Ilpurko, Ilkeekonyokie, Iloitai, Ilkaputiei, Ilkankere, Isiria, Ilmoitanik, Iloodokilani, Iloitokitoki, Ilarusa, Ilmatatapato, Ilwuasinkishu, Kore, Parakuyu, and Ilkisonko, also known as Isikirari (Tanzania’s Maasai). There was also once Iltorobo section but was assimilated by other sections. A majority of the Maasai population lives in Kenya. Sections such as Isikirari, Parakuyu, Kore and Ilarusa live in Tanganyika.

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Eastern, Lotuxo-Teso, Lotuxo-Maa, Ongamo-Maa.

Origins of the community: According to their oral history, the Maasai originated from the lower Nile valley north of Lake Turkana. They began migrating south around the 15th century, and arrived in a long tract of land stretching from northern Kenya to central Tanzania between the 17th and 18th century. They forcibly displaced the communities that had already formed settlements in the region. Some communities, mainly the southern Cushitic groups were assimilated into Maasai society. The resulting mixture of the Nilotic and Cushitic (Hamitic) populations in the area came to be referred to as Nilo-Hamitic peoples, and also include the Kalenjin and the Samburu.

The Maasai are Southern Plain Nilotes who by the middle of the 1st millennium AD had established themselves in the plains around Lake Turkana stretching from Samburu country in the east, to Karamonjong plains in eastern Uganda. From Kieru (their name for their northern plains homestead) they migrated and established themselves, for sometime, along the northern parts of Kenya Highlands where they came across the Kalenjin and other people in the highland particularly the Sirikwa who are said to have been pastoralists practising little agriculture.

The Maasai, from an early period were divided into the primarily semi pastoral people, the Iloikop (or Kuavi) and the “purely” pastoral groups, the Ilmaasai (or Maasai “proper”), both who were further subdivided into sections or “potentially autonomous tribes”. By the first half of the 18th century the Maasai were already firmly established in large areas of the Rift Valley, the Trans-Nzoia and Uas Nkishu plateau.

The Maasai people came from the south-eastern Sudan probably during the first half of the first millennium AD when the Proto-Ongamo-Maa emerged from the breakup of the Proto-Lutoko-Maa (groups of languages now spoken largely in northern East Africa). Their southward movement following a route between the Dodos escarpment in the west and Lake Turkana in the east appear to have brought them to the plains between the Nyandarua ranges and Mount Kilimanjaro.

In Kenya, starting with the 1904 treaty, and followed by the 1911 treaty the British evicted the Maasai from their territory to make room for settler ranches, subsequently confining the Maasai to present-day Kajiado and Narok districts. Maasai in Tanzania were displaced from the fertile lands between Mount Meru and Mount Kilimanjaro, and most of the fertile highlands near Ngorongoro in the 1940s. More land was taken to create wildlife reserves and national parks: Amboseli, Nairobi National Park, Masai Mara, Samburu, Lake Nakuru and Tsavo in Kenya; Manyara, Ngorongoro, Tarangire and Serengeti in Tanzania.

Natural calamities like drought and famine killed both the Maasai and their livestock in large numbers. Then came a locust invasion, which destroyed grass, cholera in 1869, which destroyed more human lives, pleura-pneumonia that wiped out cattle in the 1880s and smallpox and rinderpest, all contributing to the decline of the Maasai.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Maasai number 841,622 compared to 377,000 in 1989.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Maasai settled in Rift Valley Province’s Kajiado and Narok districts. Also in Tanzania.

In mid-19th century the Maasai territory reached its largest size covering almost all of the Great Rift Valley and adjacent lands from Mount Marsabit in the north to Dodoma in the south.

The Maasai people of East Africa live in southern Kenya and northern Tanzania along the Great Rift Valley on semi-arid and arid lands. The Maasai occupy a total land area of 160,000 square kilometres.

Housing: The traditional Maasai house was in the first instance designed for people on the move and was thus very impermanent in nature. They relied on local, readily available materials and indigenous technology to construct their houses. The houses (Inkajijik) are either star-shaped or circular, and are constructed by women. The structural framework is formed of timber poles fixed directly into the ground and interwoven with a lattice of smaller branches, which is then plastered with a mixture of mud, sticks, grass, cow dung, human urine and ash. The cow dung ensures that the roof is water-proof.

Villages are enclosed in a circular fence (an enkang) built by men, usually of thorned-acacia, a native tree. At night, all cows, goats and sheep are placed in an enclosure in the centre, safe from wild animals.

The Inkajijik (Maasai word for house) are loaf-shaped and made of mud, sticks, grass, cow dung and cow’s urine. Women are responsible for constructing the houses as well as supplying water, collecting firewood, milking cattle and cooking for the family.

Economic activities: Traditional Maasai lifestyle centres around their cattle which constitute their primary source of food. The Maasai herd goats and sheep, including the Red Maasai sheep, and cattle.

In Tanzania, cultivation was first introduced to the Maasai by displaced WaArusha and WaMeru women who were married to Maasai men; subsequent generations practised a mixed livelihood.

Traditionally, the Maasai diet consisted of meat, milk, and blood from cattle. Due to changing circumstances, especially the seasonal nature of the milk supply and frequent droughts, most pastoralists, including the Maasai, now include substantial amounts of grains in their diet. They use plants such as Acacia nilotica to make soups. The root or stem bark of the Acacia nilotica tree is boiled in water and the decoction (water in which a crude vegetable drug has been boiled and which therefore contains the constituents of the substance soluble in boiling water) drunk alone or added to soup. The mixing of cattle blood, obtained by nicking the jugular vein of cattle, and milk is done to prepare a ritual drink for special celebrations and as nourishment for the sick.

The Maasai economy is increasingly dependent on the market economy. Livestock products are sold to other groups for the purchase of beads, clothing and grains. Cows and goats are sold for uniform and school fees for children. Recently, the Maasai have grown dependent on food produced in other areas such as maize meal, rice, potatoes, cabbages (known to the Maasai as goat leaves). Those who live near crop farmers have engaged in cultivation as their primary mode of subsistence.

Trade: The Maasai conducted trade, exchanging ghee and other dairy products for grain and honey with the Okiek, the Akamba, the Agikuyu and the Luo. Iron was smelted by a special class of blacksmiths. It was women who went to the marketplace to exchange their goods.

Cycles of life Birth: In the Maasai community when a child is born the midwife plays two crucial roles: first to receive the baby welcoming him/her to the new world, and second to sever the umbilical cord thus separating the baby from the mother. As she cuts the cord she utters the following words: “You are now responsible for your life as much as I am responsible for mine”. These words serve to warn the baby that it is now a separate being responsible for itself.

The initial ceremony ends with the burying of the afterbirth. The new mother is fed with honey taken from a beehive within the area. The father of the baby or his representative must draw blood from a cow. How blood is drawn depends on whether the newborn is a boy or a girl. If its a baby boy, the father takes a rope, a bow and a blunted arrow, and makes a mock attempt at trussing a heifer before obtaining blood from the jugular vein of a bullock. In case of a baby girl, the procedure is reversed.

The house where the birth took place is then blessed either by slaughtering a sheep or using the cud that has been chewed on by either a brown or black sheep. Brown and black colours are considered sacred in the Maasai culture.

Naming: A child is named upon reaching the age of 3 “moons” [Moon – the ~30-day month is an approximation of the lunar cycle] and the head is shaved clean apart from a tuft of hair, which resembles a cock’s comb, from the nape of the neck to the forehead. A high infant mortality among the Maasai had led to children not being recognised until they reach an age of 3 moons, ilapaitin.

When a Maasai child is born, he/she is not given an official name, rather a temporary name called embolet, meaning an opening, which is used to refer to the child from the day of his birth, until the naming ceremony is held. The time of naming depends on the clan and some children may be as old as three years before the naming ceremony, called Enkipukonoto Eaji “coming out of the seclusion period” is held. During the period of seclusion, mother and baby let their hair grow long.

As the ceremony begins their heads are shaved clean. The preparations for the naming ceremony take two days with specific activities being carried out. First, two sponsors, one for the mother and another for the baby are selected to assist during the ceremony. Then two male sheep are selected, one to be eaten on each day of the ceremony. Then the mother puts a bracelet, called olkererreti, made using the right leg of one of the sheep,on the child’s right hand. At the beginning of the ceremony, the mother drinks water collected from a river using a calabash.

Once the meat is ready and all the above activities have been carried out, the mother is given the water in the calabash to drink, and the mother’s sponsor announces that the ceremony is ready to begin. The mother and her sponsor are then joined by other women who begin by examining the child’s embolet and decide on a new name based on the child’s personality. If people are fond of the temporary name, that name may be kept. The women bless the child and the new name, saying “May that name live in you” and the new name called the enkarna enchorio, becomes permanent. At the end of the ceremony the mother removes the baby’s bracelet. During the two days of the naming ceremony, the mother and her baby are honoured by being the only ones who may open and close the gate to the kraal (the Maasai typically fenced-in family settlement that contain a few houses and their cattle).

Initiation: Every 15 years or so, a new and individually named generation of Morans or Il-murran (warriors) is initiated. This involves most boys between 12 and 25, who have reached puberty and are not part of the previous age-set. The rite of passage from boyhood to the status of junior warrior is circumcision, emorata. Two days before boys are circumcised, their heads are shaved. The healing process takes 3-4 months, and the initiates remain in black clothes for a period of 4-8 months. During this period, the newly circumcised young men live in a “manyatta” a village built by their mothers.

For the initiates, junior warriors, to achieve the status of senior warrior, further rites of passage are required, culminating in the eunoto ceremony, the “coming of age”. When a new generation of warriors is initiated, the existing ilmoran will graduate to become junior elders, who are responsible for political decisions until they in turn become senior elders.

Young women undergo excision (female circumcision) as part of an elaborate rite of passage ritual in which they are given instructions and advice pertaining to their new role, as they are then said to have come of age and become women, ready for marriage. Women who will be circumcised wear dark clothing, paint their faces with markings, and then cover their faces on completion of the ceremony.

The first boys’ initiation is Enkipaata (pre-circumcision ceremony) and is organised by the father of the new age set. A delegation of boys, aged 14-16 years of age, would travel the section of their land announcing the formation of their new age-set. The boys are accompanied by a group of elders spearheading the formation of the new age-set.

A collection of 30-40 houses are built for the boys to be initiated, located in one large kraal chosen by the Oloiboni (prophet). All boys from across the region will be united and initiated in this kraal. The day before the ceremony, the boys sleep outside in the forest. At dawn they rush to the homestead and enter with an attitude of a raider. During the ceremony they dress in loose clothing and dance non-stop throughout the day. This ceremony marks the transition into a new age set. After enkipaata ceremony, boys are ready for the most important initiation known as Emuratare (circumcision).

Traditionally both boys and girls underwent circumcision shortly after puberty. However, in the 21st century, many Maasai women no longer undergo initiation through circumcision. Once boys are circumcised they become warriors and assume responsibility of security for their territory.

In order for a boy to be initiated he must prove himself to the community by exhibiting signs of a grown man, for example, carry a heavy spear or herd a large herd of livestock. A few days before the operation, a boy must herd cattle for seven consecutive days. Circumcision would take place on the eighth day. Before the operation, boys must stand outside in the cold weather and receive a cold shower for cleansing, before walking to the location of the operation amidst cheers, encouragement and sometimes threats from friends and family.

Circumcision takes place shortly before sunrise, and is performed by a qualified man with many years of experience. The healing process takes 3-4 months, and boys must remain in black cloths for a period of 4-8 months. After healing they receive the status of a new warrior.

Marriage: A marriage ceremony begins when a man shows interest in a woman by giving her a chain called olpisiai. Word of this goes round the family and community as they await him to make his intentions known. He finds women his own age to bring alcohol to the mother of the girl. This marks the first stage (called Esirit Enkoshoke) and indicates that the girl is now engaged. After some time the man makes his intentions clearer by presenting a gift of alcohol (called Enkiroret) to the girl’s father by the same women who had brought alcohol to the girl’s mother. The Girl’s father drinks the alcohol with his brothers and friends and then summons the young man and asks him to declare his interest and point to the woman he wishes to marry. Once the family agrees to the man’s request, both parties officially establish a relationship, which eventually leads to the wedding.

In the meantime the man continues to bring gifts to the girl’s family, which act as the bride’s dowry. The wedding day begins with the man bringing the bride price – 3 cows, of which two are female, one is male and all are black; and two sheep, one female (ewe) and the other male (ram). The male sheep is slaughtered during the wedding day to remove fat and oil, which will be applied to the wedding dress. The remaining oil is put in a container for the bride to carry to her new home, in the husband’s kraal.

The female sheep is given to the mother-in-law-to-be by the intended husband. From that day forth they refer to each other as “Paker”, meaning the one who gave me sheep. A calf is given to the father-in-law-to-be and from that day they refer to each other as “pakiteng” or “Entawuo”.

That morning, the bride’s head is shaved and anointed with lamb fat, she is decorated by Imasaa, beautiful beaded decorations, and puts on her wedding dress, made for her by relatives. The bride is blessed by the elders using alcohol and milk, and she is led from her family’s kraal to her new home, the kraal of her husband. There, she enters the house of her husband’s mother where she will stay for the next two days, during which time the groom may not sleep with her or eat food in the house she is staying in. After the two days, the wife’s head is shaved by her husband’s mother. This marks the end of the ceremony and the man and woman are now married.

Elders and leadership: Maasai warriors become elders after the Eunoto “coming of age” ceremony in which the mature warriors have their hair shaved off by their mothers. For about twenty years the warriors have let their hair grow, styling and dyeing it with ochre. With the shaving, their youth is behind them and are now elders. They are now allowed to marry and raise a family.

Death: Traditionally the Maasai marked the death, the end of life, virtually without ceremony, and the dead were left out for scavengers. If a corpse was rejected by scavengers (mainly spotted hyenas, known as Ondilili or Oln’gojine) it was seen as having something wrong with it, and liable to cause social disgrace, therefore, it was not uncommon for bodies to be covered in fat and blood from a slaughtered ox.

Language: Samburu. Alternate names: Burkeneji, E Lokop, Lokop, Nkutuk, Sambur, Sampur.

Samburu language is the Eastern Nilotic, North Maa language spoken by the Samburu. The word Samburu derives from the Maa word ‘saamburr’ for the leather bag the Samburu use to carry a variety of things.

The Samburu (Sampur) speak the Maa language spoken by the Maasai in southern Kenya and north-central Tanzania as well as by the Chamus (Njemps) in north-central Kenya.

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Eastern, Lotuxo-Teso, Lotuxo-Maa, Ongamo-Maa.

Origins of the community: Samburu history is intertwined with that of Kenya’s other Nilotic tribes. The Samburu are known to have originated from Sudan, settling north of Mt Kenya and south of Lake Turkana in Kenya’s Rift Valley area. Upon their arrival in Kenya in the 15th century, the Samburu parted ways with their Maasai cousins, who moved further south while the Samburu moved north.

The ancestors of the Samburu are the same proto-Ongamo-Maa group that migrated from an area situated east of the present day Juba in the southern Sudan, a migration which commenced early in the first millennium AD. Maa speaking immigrants reached the Rift Valley by the end of the 9th century and the Tanzanian territories to the south probably by the mid-sixteenth century.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Samburu number 237,179.

Geographical location of the community: After the last migration, the Samburu settled in Samburu District, Lake Baringo south and east shores; and Rift Valley Province (Chamus), and Baringo District.

The Samburu live north of the equator in Samburu district, an area roughly 21,000km². Its landscape ranges from forest at high altitudes, to open plains to desert or near desert. The main highlands are in the Leroghi Plateau (known in Samburu as Ldonyo, the mountain) at about 1,600-2,400 metres above sea level. The lowlands (Lpurkel) are hot and dry, with acacia shrub as the primary vegetation.

Housing: A Samburu settlement is known as a nkang (Maa) or manyatta (kiswahili). It may consist of only one family, composed of a man and his wife/wives. Each woman has her own house, which she builds with the help of other women out of local materials, such as sticks, mud and cow dung. Most settlements tend towards housing two or three families, with perhaps 5-6 houses built in a rough circle with an open space at the centre. The circle of houses is surrounded by an acacia thorn bush fence and the centre of the village has the animal pens away from predators.

Economic activities: The Samburu are semi-nomadic pastoralists who herd mainly cattle but also keep sheep, goats and camels. However, the combination of a significant growth in population over the past 60 years and a decline in their cattle holdings has forced them to seek supplemental forms of livelihood. Some have attempted to grow crops, while many young men have migrated to cities to seek wage labour.

Traditionally, the Samburu relied almost solely on their herds for food. Before the colonial period, cow, goat and sheep milk was a daily staple. Milk is still a valued part of Samburu contemporary diet when available, and may be drunk either fresh, or fermented. Meat from cattle is mainly eaten on ceremonial occasions, or when a cow happens to die. Meat from small stock is eaten more commonly, though still not on a regular basis. Today, they rely increasingly on purchased agricultural products – with money acquired mainly from livestock sales – and most commonly maize meal is made into a porridge. Blood is both taken from living animals, and collected from slaughtered ones. The blood is drawn by piercing the jugular vein of a cow with a spear or knife, after which the wound is resealed with hot ashes.

The Samburu diet is supplemented with roots, vegetables and tubers dug up and made into a soup.

The Samburu are a Maa-speaking group, similar to the Maasai tribe. Like the Maasai, the Samburu are nomadic pastoralists, moving from one place to another following patterns of rainfall in search of fresh pasture and water for their cattle, camels, goats and sheep. They openly graze the herds on their communal land. Every time they move, they build temporary manyattas (mud-walled, grass-thatched huts) to live in, and fence their cattle yards with thorn. Trade

Cycles of life Initiation: Circumcision for both boys and girls is one of the most important rituals among the Samburu. For boys, circumcision marks the initiation into moran (warrior) life; for girls, it signifies becoming a woman. Once circumcised, a girl/woman can be given away in an arranged marriage to start her own family.

Girls undergo female genital mutilation (FGM) between ages 10 and 13 in preparation for marriage even though they may not be married immediately. Samburu boys undergo an age-peer group ritual called rika before they graduate into morans, several years later they get married and can join the council of elders.

Initiation is done in age grades of about five years, with the new “class” of boys becoming warriors, or morans (il-murran). The moran status involves two stages, junior and senior. After serving five years as junior morans, the group goes through a naming ceremony, becoming senior morans for six years. After these eleven years, the senior moran are free to marry and join the married men (junior elders).

Marriage: Marriage is a unique series of elaborate rituals. The bridegroom must place great importance to the preparation of gifts for the ceremony, which include two goatskins, two copper earrings, a container for milk, and a sheep. The marriage ceremony is concluded when a bull enters a hut guarded by the bride’s mother, and is killed.

Language: Turkana. Alternate names: Buma, Burme, Turwana.

The Turkana refer to their language as Ng’aturk(w)ana or nga Turkana; and their land as Turkan.

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Eastern, Lotuxo-Teso, Teso-Turkana, Turkana.

Origins of the community: The Turkana people are believed to have originated from North Africa and across the Red Sea.

The Turkana tribe originally came from the Karamojong region of north-eastern Uganda. Turkana oral traditions purport that they arrived in Kenya while pursuing an unruly bull.

A camel skin container called Akutwom used for fat storage

Around 1700, the Turkana emigrated from the Uganda area over a period of years. They took over the area which is the Turkana district today by simply displacing the existing people from the area.

The ancestors of the Turkana came from Dodoth escarpment in north-east Uganda. About two to three hundred years ago, they started to move southward towards the Kagwalassi river and the Turkwell river which merge together near Lodwar and then flow into the Lake Turkana, previously known as Lake Rudolf. A Turkana legend has it that the Turkana (then known as Jie) split from their original stock, the Karamojong, following the tracks of a wayward bull which drew away most of the people.

On migrating into Kenya from the Sudan, the Turkana descended the escarpment to the Tarach River Valley and spread along the Turkwell and Kagwalasi (or Nakwehe) River Valleys to establish a new homeland in the Turkana District of today. This is a semi-desert tract, containing a few forested mountains with pastures. It is bordered by Uganda to the west, the Sudan to the north, Lake Turkana to the east, Samburu district to the south-east and Baringo and West Pokot districts to the south.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenyan census, the Turkana number close to one million, or 2.5% of Kenyan population, which makes them the third largest Nilotic group in Kenya, after the Kalenjin and the Luo, and slightly more numerous than the neighbouring Maasai.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Turkana settled in Rift Valley Province’s Turkana, Samburu, Trans-Nzoia, Laikipia, Isiolo districts, west and south of Lake Turkana; Turkwel and Kerio Rivers. Also in Ethiopia.

The Turkana are a Nilotic people native to the Turkana district in north-west Kenya, a dry and hot region bordering Lake Turkana in the east, Pokot, Rendille and Samburu to the south, Uganda to the west and Sudan and Ethiopia to the north.

Housing: The houses in which the Turkana live are constructed over a wooden framework of domed saplings (a young tree) on which grass is thatched and lashed on. During the wet season the frames are elongated and covered with cow dung. Animals are kept in a brush wood pen.

Economic activities: The Turkana are mainly nomadic pastoralists. Livestock is an important aspect of Turkana culture. Goats, camels, donkeys and Zebu are the primary herd stock utilised by the Turkana people. Livestock functions not only as a milk and meat producer, but as a form of currency used for bride-price negotiations and dowries.

The Turkana rely on their animals for milk, meat and blood. Women gather wild fruits from the bushes and cook them for 12 hours. Zebu are only eaten during festivals while goat-meat is consumed more frequently. Fish is taboo for some of the Turkana clans. Men often go hunting to catch dik dik, wildebeest, wild pig, antelope, marsh deer, hares and later go out again to gather honey.

Livestock also play an important role in payment for bride wealth, compensation for crimes, fines for fathering illegitimate children, and as gifts on social occasions.

Fishing as an economic activity is carried out by those who live near Lake Turkana.

The Turkana practice some simple cultivation consisting of planting a fast growing millet variety in low spots immediately after the rains. Wide-scale agriculture is impossible because of the climatic and terrain conditions. Livestock are used as a medium of exchange whereby they are used in payment for goods such as grain, tobacco, beads and ironware.

The Turkana have made attempts at agriculture with millet, maize, beans and gourds which are useful substitutes for milk containers carved from tree trunks. The tree trunk milk containers are sterilized by applying a paste of ashes of a certain tree to the interior to make an impermeable coat which is washable and prevents curdling.

Trade: The Turkana often trade with the Pokot for maize and beans, the Marakwet for tobacco and the Maasai for maize and vegetables.

Cycles of life Birth: At birth, the Turkana cut the umbilical cord of a baby boy with a spear symbolizing leadership, and of a girl with a knife symbolizing household work. Twins (lumuna) among the Turkana are believed to be evil and must be cleansed to prevent mischief or death. A baby born of a mother with a streak of early childhood mortality remains nameless while rituals to ensure that the baby does not die are being undertaken.

Naming: At the naming ceremony, part of the baby’s ear is snipped off.

Initiation: The Turkana, like the Luo and the Teso, do not practice male circumcision. They do not hold any special initiation rituals to mark the transition to manhood.

Initiation is the first stage of adulthood for Turkana males and occurs after a good rain season when boys are between 16 and 20 years of age. Then they must wait another 10-15 years for marriage. For the woman, marriage is the first and primary stage of adulthood. Turkana girls are usually married when they are between 15 to 20 years of age.

The Turkana do not practice circumcision at all. Boys undergo a ritual called Asapan, a cleansing and counselling ceremony in preparation for maturity/adulthood. The candidate experiences a new birth, seeing and perceiving things anew. The process involves a sponsor who later plays the role of mentor equivalent to one’s father after staying with the initiate in his home for four days. The initiate is given gifts in animal form.

Marriage: Polygamy is an acceptable way of life. A Turkana man can marry as many wives as he can afford to pay bride price for.

Among the Turkana marriages are polygamous. A man can continue to marry until he is too old to move. Some say with pride that they will continue to marry more wives until they marry Nakicholog, one who carries their ceremonial stool, Ekicholog. Nakicholog may be only ten years old and her husband as old as eighty years. She carries his stool for him wherever he goes.

Men arrange all the marriages for their daughters and sons. The first wife of a young man is often referred to as the “father’s” wife and is well respected. A woman who gives birth to more girls is held with high esteem because her husband will receive a lot of wealth in the form of dowry. A man who fathers a child out of wedlock must pay dowry and be forced to marry the girl. If the man and the girl choose to live together without officially getting married, the children will not belong to them and the parents of the girl will continue to collect dowry on every child born.

A reluctant bride among the Turkana is tied to an anthill, then the ants are summoned out by drumming on the anthill. The ants file out and bite the reluctant bride into submission.

Elders and leadership: In Turkana leadership revolves around the Council of Elders that meets at the Tree of Men to plan and resolve conflicts – both family and issues of the greater Turkana community. Males in the community participate in making the decision on cattle raids and livestock migration for pastures.

Death: In the event of death of the father or mother in a homestead, they are buried in the ground on which their hut is built (the hut will be pulled down). The eldest son inserts a piece of butter in the mouth of the dead person and pronounces “Sleep in the cool earth and do not be angry with us, who remain on this earth!” passing near the mound, acquaintances and villagers will pay homage to the dead person throwing pinches of tobacco and mouthfuls of indigenous beer or milk. Upon death, the other people do not have any right to a burial but are abandoned in the savannah to the hyenas and vultures.

Language: Teso. Alternate names: Ateso.

They are also known as Iteso, the people of Teso. They are an ethnic group in eastern Uganda and western Kenya. Teso refers to the traditional homeland of the Iteso, and Ateso is their language.

Linguistically, the Teso belong to the Teso-Karamojong branch of Eastern Nilotic languages.

Language family: Nilo-Saharan, Eastern Sudanic, Nilotic, Eastern, Lotuxo-Teso, Teso-Turkana, Teso.

Origins of the community: Teso traditions relate that they originated somewhere in what is now Ethiopia and migrated south-west over a period of centuries. They were part of a larger group of Nilotic peoples who migrated from Sudan in several waves. A splinter of this group later formed a branch called the “Karamojong Cluster” or Ateker. The Ateker further split into several groups, including Jie, Turkana, Karamojong and Teso.

The Teso established themselves in present-day north-eastern Uganda, and in the mid-18th century began to move further south. During the course of this latter migration, conflicts ensued with other ethnic groups in the region, leading to the split of Teso territory into a northern and southern part. In 1902, part of eastern Uganda was transferred to western Kenya leading to further separation of Teso.

The Iteso belong to a family of people which may be called Ateker (people of one language) formerly called Nilo-Hamite peoples. The Ateker are composed of nine major peoples: the Iteso, Karamonjong, Jie and Dodoth in Uganda; the Turkana and Iteso of Kenya; the Toposa, Jie and Donyiro of the Sudan. The Ateker speak mutually intelligible dialects of the same language.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Teso number 338,833.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Teso settled in Western Province’s Busia District.

Northern Teso occupy the area previously known as Teso district in Uganda, while the Southern Teso live mainly in the districts of Tororo and Busia in Uganda, and Busia district in Kenya’s Western Province.

The Njemps (IlChamus, Chamus or Tiamus), are a Maa people living south and southeast of Lake Baringo, Kenya. They number about 19,000 and are closely related to the Samburu living more to the north-east in the Rift Valley Province.

Their language is one of the Eastern Nilotic Maa languages, closely related to the Samburu language (between 89% and 94% similarity). The language is considered a Samburu dialect by some. Together, Samburu and Camus form the northern division of the Maa languages.

In their oral traditions, the Camus economy developed from foraging and fishing to a sophisticated system of irrigation, and subsequently mixed with pastoralism under the influence of Samburu immigrants and neighbouring Maasai. Their culture and social organization metamorphosed as a result of assimilation and integration with neighbouring cultures. Western-style capitalism in post-colonial Kenya and other environmental challenges constinues to polarise have negatively impacted the majority of Camus and several other Northern Kenya communities.

Language: Nubi. Alternate names: Ki-Nubi, Kinubi. The Nubi language is a Sudanese Arabic-based creole language. The Nubi language is spoken in Uganda around Bombo, and in Kenya around Kibera.

Nubi is Arabic, since about 90% of its vocabulary is of an Arabic nature. It is termed as a creole, since many of its structural and developmental features resemble those of known creoles.

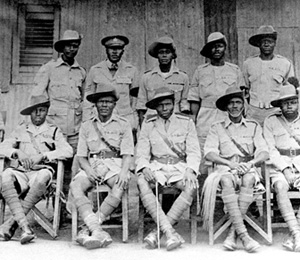

Nubian first world war soldiers

Origins of the community: Nubi language speakers are descendants of Emin Pasha’s Sudanese soldiers who were settled in their current location by the British colonial administration.

Most of the Nubi people originated from Egyptian military stations which were scattered all over along the Nile, from Shilluk and the country in the North, to the Mahdi and Acholi in the south and the Makaraka (a branch of the Zadze tribe) in the west and a part of the province of the Equatorial. The dominant group, and not necessarily the majority group were Egyptians, and Sudanese Arabs as high officers and Negroid elements captured previously from the Nuba mountain and Southern Sudan who had been trained as soldiers. The Nubi also included captured slaves and slaves given in payment to the soldiers or tribesmen from neighbouring villages that had come to share in the cultural life of the stations. These elements taken in total formed the main ancestors of the East African Nubi communities.

The Nubi originated in the Sudan and spread to various East African countries due to their involvement with the British army. Others stayed after their escape from slavers as they were being driven from their homes to the coast.

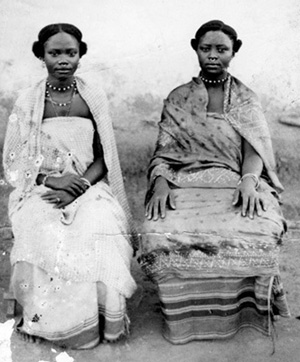

Nubian women

The history of the Nubi goes back to the late 1800s in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan. In the last decades of the Ottoman Empire, the British administered “the Sudan” jointly with the virtually autonomous Ottoman Turkish province of Egypt. A religious leader called the Mahdi led a rebellion against the British-Egyptian government. After the British victory, Sudanese soldiers who had agreed to join the British forces were rewarded with land in Kibera, now a heavily populated slum area in south-western Nairobi. The Nubi are still strongly associated with Kibera, though this slum area now includes dense populations of people from virtually every tribe in Kenya. Some Nubi also settled in Uganda.

Although the name ‘Nubi language’ literally means Nubian, it bears no relation to the Nubian languages spoken by the Nubian groups in the south of Egypt and north of Sudan; its name derives from a misuse of the term “Nubi”. In fact, most of the soldiers who came to speak originally came from Equatoria, in South Sudan.

The Nubi were relocated by the British Colonial Administration from the Nuba mountains in Sudan. They first arrived in Kenya in the late 19th century. In 1904, the British Colonial Administration created a settlement in Kenya for discharged Nubian soldiers who had been drafted into the King’s African Rifles from what is now Sudan. The settlement, located near Nairobi, became known as Kibera. Ironically, Kibera which comes from the word kibra in the Nubi language and means ‘land of the forest’ has now become one of Africa’s largest slums. A majority of Nubians were initially settled in Kibera, but today only 50% of the community live there. The rest mostly reside in so-called Nubian villages across Kenya.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Nubi community in Kenya number 15,463.

Nubian family

Geographical location of the community: Kibera, outside Nairobi’s central business district.

Some factors which influenced the dispersal of the Nubi to where they are today includes the First World War (1914-1918), the development of the East African Railways in Uganda, army transfers and commercial opportunities. When the war broke out, many Nubi came to Kenya from Uganda and some eventually went to Tanzania to fight the Germans. After demobilisation, some chose not to return to their earlier homes and in recognition of their services in the war, they were given plots or settlement parishes. That is how Nubi settlements like Kibera in Nairobi, Majengo-Sokoni in Mombasa, Iringa in south-western Tanzania and Dar-es-salaam came to be established. Nubi neighbourhoods in Uganda include Bombo, Naguru and Kibuli in Kampala and Kitibulu near Entebbe.

Colourful Nubian wedding dress at Kibera wedding.