- Home

- The Universe »

- Human Origins »

- The first ape men »

- Proconsul

- Nakalipithecus

- Chororapithecus

- Sahelanthropus

- Orrorin Tugenensis

- Ardipithecus Kadabba

- Paranthropus aethiopicus

- Australopithecus Anamensis

- Ardipithecus Ramidus

- Australopithecus Afarensis

- Australopithecus Africanus

- Australopithecus sediba

- Paranthropus boisei

- Paranthropus robustus

- Kenyanthropus platyops

- Australopithecus garhi

- Stone age cultures & technologies

- Stone Age ancestors »

- Out of Africa Migration

- The first ape men »

- Civilisation »

- Peoples & Cultures »

- Interactive Exhibitions »

- Museums of Kenya »

Central & Eastern Bantus

Central and Eastern Kenya region Bantus include:

The Mbeere and the Embu were once one people.

Oral history has it that the Mbeere were forced to split from the Embu following a dispute which came about during a mock battle in which the two peoples honed their skills. Instead of swords, they used fighting sticks, but one fateful day, some Mbeere decided to use real swords, and ended up killing and injuring several Embu warriors. As a result, they were expelled, and were forced to settle in the less fertile Kiangombe Hills. Another version of the same story, recounted by elder quoted by Ciarunji Chesaina, says: “Now the Embu used to beat the Mbeere very often. A Mbeere person could not utter a word when an Embu person was talking. There were even times when an Embu person could eat food while a Mbeere was just watching and only gave him some when he himself was full. Mbeere people had nicknamed Embu people, “The Clan of Rebels” because of their stubbornness, while the Embu had nicknamed the Mbeere, “The Clan of Famine” because of their being denied food. Now, one time, Embu and Mbeere made a date to fight and finish all their conflicts. Now on the day of the fight Mbeere brought sticks as their weapons while Embu brought swords disguised as sticks. The war which was fought! The Mbeere were beaten! The Embu pushed the Mbeere until Kiethiga, while the Embu went to live in Muthiru. That is when the Mbeere started to live in the sandy land where crops cannot grow, while the Embu built their homes near the forest on productive land.”

Language: Gichuka. Alternate names: Chuku, Suka.

Language family: Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Southern, Narrow Bantu, Central, E, Kikuyu-Kamba (E.20), Meru.

Origins of the community: They are commonly considered to be a subgroup of the Meru, but they actually have more in common with the Embu. Oral history says that the Chuka were children of Ciangoi, who was a sister of the Embu ‘founding mother’ Cianthiga. They migrated south from the Nyambene Hills some time in the sixteenth or seventeenth century.

Gichuka is linguistically closer to Kiembu than Kimeru.

According to Cuka traditions, the Cuka, Aembu and Tharaka are very closely related. They are said to be descendants of three sisters who migrated from Tigania or Igembe or both places. On leaving Tigania and Igembe, they are said to have settled around Ntugi forests. The mother of the Tharaka, Cia-Mbandi, was left there and she gave offspring to the Tharaka, while Cia Nthiga (the Eve of the Aembu) and Cia Ngoi (the Eve of the Cuka) pressed ahead and settled at Igambang’ombe. Cia Nthiga and Cia Ngoi apparently quarreled at this stage and the former crossed the Tharia and Thuci rivers into modern Embu land, while the latter went up the ridge to settle at Magumoni.

Other anthropoligical studies report that the Chuka – Fadiman Chuka traditionally kept their cattle concealed in pits, a trait he believes was learned from the Umpua. The Chuka who also claim to have been in the coast Mboa are descended from an indigenous people and another group, which was composed, of the migrants from Ethiopia who later formed a group called the Tumbiri. According to the to Mwaniki, all the mount Kenya people have elements of the Tharaka and Tumbiri within them. While the Meru named the leader who got them out of Mbwaa as Koomenjwe, the Chuka stress the “Mugwe” as their leader. Koomenjwe was also called mũthurui or Mwithe.

A study by M. A. Kabeca gives the names Pisinia, Abyssinia, Tuku, Mariguuri, Baci, Miiru, and Misri as synonyms of Mbwaa with some informants stating the above location to be the place of the “Israels.” The Embu were called Kembu and came as hunters looking for ivory”. The available oral evidence demonstrates that the language spoken by the mount Kenya people may be indigenous, from the south or east but the main corps of the people came from the north.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Chuka settled in Eastern Province’s South Meru district. Housing

Economic activities: The Chuka are agriculturalists, utilising the favourable soil and climate of the eastern slopes of Mount Kenya. They terrace the crop plantations.

The cash crops grown in Chuka region are coffee, tea and pyrethrum. Subsistence crops include maize, beans and bananas.

Language: Gikuyu. Alternate names: Gekoyo, Gigikuyu, Kikuyu.

The word ‘Kikuyu’ is the Swahili form of the proper name and pronunciation of Gĩkũyũ.

Language family: Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Southern, Narrow Bantu, Central, E, Kikuyu-Kamba (E.20).

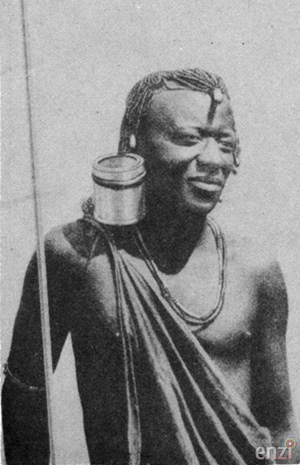

Kikuyu man

Origins of the community: The ancestors of the Kikuyu are said to have come from the North, from the region beyond the Nyambene Hills to the north-east of Mount Kenya (Kirinyaga), which was the original if not exclusive homeland of all central Kenya’s Bantu-speaking people, viz. the Meru, Embu, Chuka, Kamba and possibly Mbeere. They are believed to have arrived in the hills as early as the 1200s.

By the early 1600s, they were concentrated at Ithanga, 80kms south-east of the mountain’s peaks at the confluence of the Thika and Sagana rivers.

As Ithanga’s population increased, oral traditions of all the tribes agree that the people began to fan out in different directions, eventually becoming the separate and independent tribes that exist today. The Kikuyu moved west to a place near present-day Murang’a.

The original inhabitants of Kikuyuland, it is said were the Thagicu, who practised iron-working, herded cattle and sheep and goats and hunted.

The Kikuyu community creation myth: According to the oral tradition of the Kikuyu the founder of the tribe was a man named Gikuyu. One day, God (Ngai) gave him a wife called Mumbi and commanded them to build a homestead at the valley with a unique bird species called “Nyagathanga”. The location is to the south-west of Mount Kenya (Kirinyaga) and is called “Mukurwe wa Nyagathanga” (translated as Valley of Nyagathanga). Some versions of the story say that Ngai first took Gikuyu to the top of Kirinyaga to behold the land that he was giving them.

Mumbi bore nine daughters, who married and had families, and which eventually became clans. These clans -the true ancestors of the Kikuyu- are actually called the ‘full nine’ or ‘nine fully’ (kenda muiyuru), for there also was a tenth daughter, who descended from an unmarried mother in one of the other nine clans (which suggests the later amalgamation of at least one other people into the Kikuyu). Until recently, it was a common taboo for anyone to give the exact number of their children; violating the taboo -any taboo- would portend a bad omen.

The homestead (mucii) comprised of several families, not necessarily related by blood, but who lived and worked together for everyone’s benefit. Several homesteads formed a patrilineal sub-group or ‘community unit’ called mbari, comprising of males and their wives and children ranging from a few dozen to several hundred persons. These in turn gathered into the nine (or ten) clans called muhiriga, who were united by their shared matrilineal descent from one of the nine (or ten) daughters of Gikuyu and Mumbi, and hence their names. The main nine clans were the Achera, Agaciku, Airimu, Ambui, Angare, Anjiru, Angui, Aithaga, and Aitherandu.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Kikuyu number 6,622,576. The Kikuyu make up about 23% of Kenya’s total population.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Agikuyu settled around Mt Kenya and the central highlands, including Nyeri, Murang’a, Kiambu and Kirinyaga regions of Kenya.

The Agikuyu ancestral and spiritual homeland is in the present Central Province. Natural landmarks mark the boundaries of the area. To the north is Kirinyaga (Mount Kenya); to the west is the Gikuyu escarpment of the Rift Valley, which merges to the north with the Nyandarua range and to the east and south is Kianjahi hills (Ol Donyo Sabuk) and Ngong hills respectively. The area has ample rainfall, which averages from 1750mm in the highlands and 1000mm in the lower lands per year.

Housing: Traditionally, the Kikuyu lived in separate domestic family homesteads, each of which was surrounded by a hedge or stockade and contained a hut for each of the man’s wives. The houses were made of thatch, sticks and baked mud, often raised on poles.

The wives huts are each partitioned into seven parts: the woman’s sleeping place (ũrĩrĩ), a place for storing food (thegi), a place where girls sleep (kĩrĩrĩ), goats that graze in the field are kept on the left side of the woman’s bed. At the centre of the house is a cooking place with a traditional hearth of three stones (riuki).

The family lived in a homestead with several huts for different family members. The husband’s hut was called ‘thingira’, and it was where the husband would call his children in for instruction on family norms and traditions and he would also call his wives for serious family discussions. Each wife had her own hut where she and her children slept. After boys were circumcised (at puberty) they moved out of their mother’s hut into the young men’s hut.

Economic activities: The chief economic activity for the Kikuyu is cultivation (farming). They grow bananas, sugar cane, arum lily, yams, beans, millet, maize and a variety of vegetables. This is done both on small scale and large scale. Cash crops grown include: coffee, tea and horticultural produce. They rear cattle, goats, sheep and chicken.

The original pattern of migration and the subsequent system of land acquisition governed the land tenure that emerged. Available traditions indicate that the vanguard of the pioneers would hunt and trap wild animals, collect wild honey or hung beehives on trees in the forests. Pastoralists and agriculturalists followed later.

Trade: The Kikuyu came into constant contact with the Maasai, but they were neither conquered nor assimilated by them, they engaged in trade (as well as sporadic cattle raiding). Owing to these interactions Nilotic social traits such as circumcision, clitoridectomy and the age-set system were adopted; the taboo against eating fish was accepted; and people intermarried so much so that more than half of the Kikuyu of some districts are believed to have Maasai blood in their veins.

The Kikuyu having settled in fertile lands produced food far in excess of what they needed to feed themselves. The Embu, Mbeere, Chuka, Kamba and hunter-gathering Okiek (Ndorobo), whose lands were less fertile, and were prone to drought and famine, traded with the Kikuyu for food. In return for supplying food, the Kikuyu received all manner of goods ranging from skins, medicine and ironwork from the Mbeere, livestock and tobacco from the Embu, and salt and manufactured trade goods brought up from the coast by the Kamba, with whom the Kikuyu had their most important trading relationship.

The Gikuyu traded with the Athi who were expert elephant hunters and hence important source of ivory to the Gikuyu who then sold the ivory to the Akamba and the Maasai in exchange for goats. A good piece of ivory of about 10 feet (3.05 metres) in length could fetch between fifty and a hundred goats when sold to the Akamba and Swahili traders. The Akamba were chiefly middlemen who sold the ivory to the Nyika (Mijikenda) people who in turn sold the goods to the Mombasa traders.

Cycles of life Boys and girls were raised differently: girls would help out their mothers by taking care of household chores, tend shamba (farm) crops and younger children, while boys were expected to help out by herding the animals.

The age-sets (mariikaa) served as the primary political institutions in traditional Kikuyu life for they united everyone of similar age, who together held a set number of responsibilities and social duties for the Kikuyu as a whole, such as defence (the role of the warrior age set) and its judgement (exercised by elders). Groups of boys were initiated each year, and were ultimately grouped into generation sets that traditionally ruled for anything between five and thirty years.

Birth: During childbirth men hang around the fridges of the homestead as they were not allowed near where the child was being born. Once the midwife announced the sex of the child the men and others were informed through ululations: five ululations meant that the child was a boy and four signified a girl.

It was considered bad luck to speak openly about the coming birth of a child, because it was thought that evil spirits would take the child.

After birth, mother and child remained in seclusion until the umbilical cord of the child was ‘cut’. Naming was held after the seclusion was over.

Naming: The family identity is carried on in each generation by naming children in the following pattern: the first boy is named after the father’s father, the second boy after the mother’s father, the first girl is named after the father’s mother, the second after the mother’s mother.

Education: From the time of birth the child belonged to the community. The role of bringing up the child and caring for the mother was communal. The child’s grand parents and siblings kept the child company and taught him the ways of the people. Girls are taught by their grandmothers and boys by the grandfathers. Oral narratives, songs, poems, riddles, proverbs were some of the tools used to inculcate social morals and values in the young.

Toys were improvised for example boys make cars using tins and wires, and make balls using polythene papers or rags.

The Gikuyu family was the centre of all religion, and family worship was more important to the Agikuyu than public worship, which was conducted only on very special occasions. It was from the families that Gikuyu children obtained most of their moral education imparted through stories and riddles. Fathers spent much of their evenings talking to their sons, and mothers to their daughters. Girls learned to do agricultural work, to cook and to help their mothers in their domestic chores; they prepared themselves to become future mothers by looking after their small brothers and sisters. Boys learned to look after livestock, and were prepared for the future defence of the country and for raiding the Maasai for livestock.

Initiation: To the Agikuyu, initiation conferred a new social status. Childhood behavioural values were cast off and the initiated became full members of the community. This was also an opportunity to teach group traditions, religion, folklore, mode of behaviour, taboos, correct sexual behaviour, and duties of adulthood.

As adult members of the community the male initiates became members of the junior warrior group and could defend the country together with the senior warriors. The entire warrior corps formed a reservoir of able-bodied men for performing other public functions. They acted as executive officers to the elders, being entrusted with such policing duties in the markets during festivals, the arrest of habitual criminals and the calling of public gatherings during which rules and prohibitions were promulgated and other pronouncements made. The warriors also performed manual tasks such as clearing of virgin land, building of houses,cattle bomas (kraals) and planting bananas, sugar cane and yams.

Circumcision is the rite of passage from childhood to adulthood. Traditionally both boys and girls underwent the ritual cut. After circumcision, the initiates were put in seclusion throughout the period of recovery. They were taught in groups: the girls by an elderly woman and the boys by an elderly man. The teaching was aimed at preparing them to be responsible men and women in the community.

Traditionally there was a circumcision ceremony for boys and girls by age grades of about five-year periods. All the men in that circumcision group would take an age-grade name. Times in Kikuyu history could be gauged by age-grade names. It is thought that the early Thagicu, one of the ancestral groups of the Kikuyu borrowed this system from Cushitic and Nilotic peoples.

Boys were circumcised at the age between fifteen to eighteen years, while girls were circumcised after their first menstruation between twelve and fifteen years. For a boy circumcision was a public ceremony, to make certain that no candidate showed any signs of fear or cowardice. For the females, circumcision, act of cutting off the clitoris, was a private affair, and meant to reduce the sex drive of the female as she matured.

After boys were circumcised, they moved out of their mother’s hut into the young men’s hut.

Marriage: Women who engaged in sex before marriage, had affairs, or got pregnant could only be married as a second wife and were commonly referred to as ‘Gĩchokio’.

Elders and leadership: The political organisation of the Kikuyu people was closely interwoven with the family and the riika. A young man after initiation through circumcision automatically entered into the National council of junior warriors (njama ya anake a mumo). After 82 moons or 12 rain seasons after the circumcision ceremony the junior warrior was promoted to the council of senior warriors (Njama ya ita). These two councils would be called upon to protect the tribe in case of external aggression. The council of senior warriors was in addition an important decision making organ.

Upon marriage a man was initiated into a council called kiama kĩa kamatimo. This was the first grade eldership and it denoted elders who were also warriors. At this stage the man plays the role of observer of senior elders, they are required to assist in proceedings by carrying out menial tasks like skinning animals, being messengers, lighting fires or carrying ceremonial articles.

When a man had a son or daughter old enough to be circumcised, he was elevated into another council called the council of peace (kiama kĩa mataathi). He assumed the duty of peace-maker in the community.

When a man had had practically all his children circumcised and his wife (or wives) had passed child-bearing age he reached the last and most honoured status – a council known as kiama kĩa maturanguru (religious or sacrificial council). The elders of this grade assumed the role of ‘holy men’ -high priests, all religious and ethical ceremonies were in their hands.

As a symbol of their office, senior elders wore earrings (icũhĩ cia matũ or ngocorai) and carried staffs and mataathi or maturanguru leaves tied with a twisted string. The elders were the highest authority in the land, and carried out legislative, executive and judicial functions. The most significant function of the elder-councils was the administration of justice, which was carried out through arbitration by a court constituted by the kĩama (council). The primary purpose of the judicial purpose was to maintain peace and stability in the society.

Death: Traditionally, the dead were not buried rather they were left in the bush for the wild animals to eat them. This practice died out in the early 1950s. The Kikuyu did not believe in the after-life, but they believed in the living dead. The spirits of the living dead would come and torment the living if they are not appeased. The living dead were appeased with traditional beer that was prepared and regularly poured at the three stones where it was cooking.

The Gikuyu interred only elders and the rich, since the burial of young people was symbolically seen as burying the nation’s future. Corpses of the poor and those who had not attained eldership were normally abandoned in the bushes for scavengers to devour. Baring special circumstances, such as death occuring within the compound where circumcision initiates were being hosted, entering a deceased person’s hut or physical contact with a corpse was deemed to be contaminating and required cleansing by a medicine man.

Near-death adults, other than male elders and elderly widows who had co-wives, were evacuated from the homestead and secluded in shelters in the bushes near the village set aside for this purpose. Close relatives tended them until they died but if they recovered, a ceremony to purify and welcome them back was held.

For those who were buried, a ram’s skin was used to cover the body before the grave was filled with soil and a tree planted on top.

Language: Kimîîru. Alternate names: Kimeru, Meru.

Kimeru dialects include Imenti, Igembe, Tigania, Igoji, Mwimbi, Chuka, Muthambi and Tharaka.

Language family: Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Southern, Narrow Bantu, Central, E, Kikuyu-Kamba (E.20), Meru.

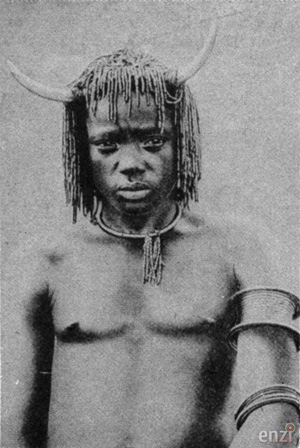

Young Meru man

Origins of the community: The Meru of Kenya say that before they settled in their present land, they had come from the far North, ruteere rwa urio; they believe that they migrated from Misri (Egypt). Other interpretations of Meru history incorporates aspects of Meru mythology and spans about three centuries. There are no written records for the first two centuries and what may be learned must come from memories of the community’s elders. The predominant tradition has to do with a place called Mbwa. This tradition tells how the Meruan ancestors were captured by the Nguuntune (the “red people” literally the “red clothes” generally taken to mean the Arabs) and taken into captivity on the island of Mbwa. Because the conditions were intolerable, secret preparations were made to leave Mbwa. Some oral traditions sources place the location of Mbwa to present day Yemen, while others identify it with Manda Island near Lamu. When the day came to leave Mbwa a corridor of dry land is said to have been created for the people to pass through the Red Sea. They later followed a route that took them to the hills of Marsabit, eventually reaching the Indian Ocean coast. There they stayed for some time; however, due to climatic conditions and threats from the Arabs, they travelled farther south until they came to the Tana River basin. Most traditions say most went as far south as Tanzania until finally reaching the Mount Kenya area.

The Meru people are divided into seven sections namely; the Igoji, Imenti, Miutuni, Igembe, Mwimbi and Tharaka. The Chuka and Tharaka are now considered Meru but have different oral histories and mythology; however, linguistically, they are Meru.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Meru number 1,658,108.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Meru settled in the Meru region of Kenya. They live primarily on the fertile agricultural north-eastern slope of Mount Kenya, in the Eastern Province of Kenya. The Meru region consists of approximately 13000km² stretching from River Thuci in the south which is the traditional boundary between the Meru and Embu people to Isiolo district in the north.

The name “Meru” refers to both the people and the location. In the years prior to 1992 there was only one geopolitical district for the Meru people, then the area was divided into three: Meru, Nyambene, and Tharaka-Nithi.

Housing: Each homestead consisted of small cylindrical thatched houses, granaries, and a circular animal compound. Every married woman had a separate hut and garden. From the 1950s rectangular houses constructed of timber with corrugated iron roofs replaced cylindrical-conical homes and animals were pastured in enclosed paddocks.

The Ameru lived in villages of several families. Each family owned a piece of arable land on which they cultivated crops and kept livestock. At the family level, the father and head of the family resolved disputes; he lived in his own house, which was known as gaaru.

Economic activities: They Ameru in the highland areas of Meru traditionally grew a mixture of food crops such as bananas, yams, cassava, pumpkins, millet, sorghum, and sugar cane, and kept domestic animals – cattle, sheep and goats. Tobacco, gourds, and miraa, a mild stimulant, were also grown. The semiarid environment of lowland Meru were primarily reliant on hunting, bee-keeping, and plant-gathering. During the 1940s, the colonial government promoted new food varieties, leading to widespread adoption of maize as a staple crop.

Cultivation of export crops such as coffee, tea, sisal, wheat, sugar cane was initially prohibited by European settlers. The ban on coffee cultivation was lifted during the 1930s bringing markets, factories, and roads to the area. Tea was introduced in the 1960s and it is grown in the high altitude areas of the district. Other cash crops include cotton, maize, beans, sorghum, and millet.

Trade: During the colonial period commercial markets operated by Indian and Swahili traders sold foodstuffs as well as bags, mats, knives, implements, skins and hides. Miraa remains the major cash crop in low-land areas and is widely traded with coastal regions and Somalia.

Cycles of life Birth: Traditionally, a newborn child was immediately offered to God. The mother would hold her newborn, face either of the sacred mountains – Mount Kenya or Mount Njombeni (Nyambene), offer the child to God by spitting on it (spitting saliva-gwikia mata-is a sign of good wish and blessing).

Education: Between the age of five and seven, children underwent an educational rite (kiama kia ncibi) during which they were instructed in basic social values.

Traditionally, boys went through several stages of formalised instruction by the council (kiama). After circumcision boys underwent a period of seclusion and education on communal obligations, military responsibilities, and sexual relations. Similarly, women’s councils (ukiama) provided teaching on acceptable behaviour and marital duties to young girls. In the 21st century the majority of socialisation occurs through the extended family, schools, and churches.

Initiation: Through circumcision, both boys and girls attain adulthood, and all the respect and responsibilities that go along with it. It marks their initiation not just into adulthood, but also into society and thus full membership to the tribe.

Boys’ as well as girls’ circumcision was preceded by two preparatory rituals: the time for marking the spots where ear-hole perforation would be done (igiita ria kugerua matu), and the time for actual perforation of the ears (igiita ria guturwa matu).

In traditional rural areas the Meru have fairly strict circumcision customs that affect all of life. From the time of circumcision boys no longer have contact with their mother. A separate hut is built for the sons.

Once circumcised, girls no longer have contact with their father.

Upon circumcision, each adult, both male and female, became a member of a particular age-set, depending on when they were circumcised. Each age-set comprised several years, meaning for example a man circumcised seven years after another might belong to the same age-set.

Marriage: A young woman was married off soon after healing from her circumcision. During the wedding, the bridegroom delivered four gourds of beer and some snuff to the clan so that her parents might bless their daughter as she left the seclusion hut and before she left them.

Postmarital residence is patrilocal (a marriage pattern in which the couple lives with the husband’s family). Women’s rights and obligations became embodied within the husband’s patrilineage after marriage.

Elders and leadership: The elders of the tribe were divided into three ranks: the Areki, which comprised both men and women; the Njuri-Ncheke (also spelled Njuuri Nceke); and the Njuri -Mpingiri. To become a member of the Njuri-Ncheke was the highest social rank to which a man could aspire. The functions of the Njuri-Ncheke were to make and execute tribal laws, to listen to and settle disputes, and to pass on tribal knowledge and rites across the generations in their role as custodians of traditional culture.

Death: Traditionally, the majority of the Meru did not bury the dead but abandoned their bodies in the bush, believing that a corpse was contaminated. The person who disposed of the body had to undergo a cleansing and sexual ritual. During the colonial period, these practices ended and burial became a legal requirement.

Language: Kamba. Alternate names: Kekamba or Kikamba. The speakers of this language call themselves Akamba and the place of residence, Ukambani.

Language family: Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Southern, Narrow Bantu, Central, E, Kikuyu-Kamba (E.20).

Kamba woman

Origins of the community: The Akamba creation myths tell how Ngai Mulungu (‘the All-Powerful God’), Ngai Mwatuangi wa nzaa (finger-divider), made the first pair of husband and wife, and brought them out of a hole in the ground or from the sky according to a second version.

Historical records hold that the Kamba migrated into Kenya in the 14th century and settled in the Taveta area before migrating northwards to the Nzaui Hills in the present day Makueni district. A dispersal of the community occurred in the 17th century with some moving to Mbooni and others to Kitui, Mwingi and the fridges of Central Province. The Mbooni group later moved to present day Machakos and Kangundo districts.

Akamba history is divided into four important phases within a period of four hundred years. The first is the Kilimanjaro settlement and migration phase; the second phase is the Mbooni settlement in Ukamba; the third phase is the dispersal of the Akamba from Mbooni hills; and the fourth phase is the development and decline of Akamba trading prior to colonial occupation.

The Kilimanjaro phase: settlements around Kilimanjaro seem to have been established during the first half of the 17th century. A majority of Kamba traditions state that in the plains the Akamba were cattle keepers and that to compensate for the inadequate water supply for their cattle, they constructed rain ponds. They also engaged in hunting and trapping of small game and collecting fruits and roots to supplement the diet of meat from game and cattle.

Mbooni settlement phase and the dispersal: During the last decade of the 16th century, the Akamba settlers began to leave the Kilimanjaro plains. The cause of this migration was partly the constant raids by the aggressive semi-pastoral Iloikop Maasai, the Wakuavi. From Kilimanjaro plains, the Akamba entered the present Ukambaland by scaling the steep slopes of the Chyulu hills which they found to be rocky and not well supplied with surface water. They soon left Chyulu hills for a short stay in Kibwezi where long seasonal droughts forced them to move northward and settled around the towering rock of Nzaui for a short period of about thirty years. From here majority of the Akamba groups moved on rapidly to Mbooni hills and only some splinter communities remained behind. After about one hundred years, some of the Akamba people returned in large numbers to this southern area to settle.

Mbooni hills was a region of secluded woodlands, thick foliage and forests which offered the Akamba natural fortifications against raids. In about 1715 some groups of Mbooni people began to move from the hills across the Athi River in central Kitui. Between 1740 and 1780 and particularly 1760, heavy migration to the eastern reaches of Ukamba as well as to the north took place. The movement was fuelled by depletion of soil fertility in the intensely cultivated Mbooni region, aresurgence of pastoralism, local feuds and strife between sections of the Akamba community.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Kamba number 3,893,157. The Akamba make up 11% of Kenya’s total population.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Akamba community settled in South central, Eastern Province’s Machakos and Kitui districts; and Coast Province’s Kwale District.

The Kamba are a Bantu ethnic group who live in the semi-arid Eastern Province of Kenya stretching east from Nairobi to Tsavo and north up to Embu, Kenya. This land is called Ukambani.

In Kenya, Kamba is spoken in four major regions of Kamba Land. These regions are Machakos, Kitui, Makueni and Mwingi. The Machakos variety is considered the standard variety of the four dialects.

Neighbouring people to the north-west of Kambaland are the Agikuyu and to the north are the Tharaka and Mbeere. To the south-west of the traditional Akamba country are the Maasai. To the north and east are the Boran, Galla, the Pokomo and other small nomadic groups known as Boni, Sanye and Aliangulo. Other groups of Akamba numbering hundreds of thousands, live outside Ukamba as Akamba communities in Rabai near Mombasa, Taita Taveta and Kwale Districts and another group in central Tanzania.

Housing: A homestead was the smallest social unit. It was usually a stockade (an enclosure or pen made with posts and stakes) around the home of each married man, which contained the huts of his wives. Outside the entrance of several family homesteads was a thome, a shaded open space, where men sat and discussed everyday events. Thome was the basic political unit.

Economic activities: In the Akamba community women cultivate the land. In the cooler regions of Ukambani such as Kangundo, Kilungu and Mbooni crops such as maize, millet, sweet potatoes, pumpkin, beans, pigeon peas, greens, arrowroots, cassava and yams are grown.

Trade: The Kamba were involved in long distance trade during the pre-colonial period. There was barter trade between the Kamba and the Kikuyu, Maasai, Meru people in the interior, and the Mijikenda and Arab people of the coast.

As long-distance traders they participated in commerce from the coast to Lake Victoria all the way up to Lake Turkana. The main trade items were ivory, beer, honey, iron weapons, ornaments, and beads.

Cycles of life Birth: For the Akamba of Kitui and Machakos, the birth rite of passage introduces the baby into the community. The birth process begins with conception and continues till the actual birth. During childbirth, the physical cutting of the umbilical cord and the ritual symbolise a separation of the newborn from its former life in the womb and the introduction into a new state.

Naming: The naming ceremony for the newborn is performed on the third or fourth day after birth. This ceremony is called “Kuimithya” literally meaning to make fully human. Before the naming ceremony the newborn is merely referred to as kaimu (literally a small spirit). The climax of the naming ceremony is the actual pronouncement of the name of the newborn normally by the grandmother or in her absence by a close elderly woman relative.

The first four children, two boys and two girls, are named after the grandparents on both sides of the family. The first boy is named after the paternal grandfather and the second after the maternal grandfather. Girls are similarly named. A woman cannot address her parents-in-law by their first names yet she has to name her children after them. To solve this problem, a system was adopted in which names given were descriptive of the quality or career of the grand parents.

After the four children are named, whose names were more or less predetermined, other children could be given any other names, sometimes after other relatives and/or family friends on both sides of the family. Occasionally, children were given names that were descriptive of the circumstances under which they were born, “Nduku” (girl) and “Mutuku” (boy) meaning born at night, “Kioko” (boy) born in the morning, “Mumbua/Syombua” (girl) and “Wambua” (boy) for the time of rain, “Wayua” (girl) for the time of famine, “Makau” (boy) for the time of war.

Children were also given affectionate names as expressions of what their parents wished them to be in life. Such names include “Mutongoi” (leader), “Musili” (judge), or “Muthui” (the rich one), or “Ngumbau” (hero, the brave one). Wild animal names like Nzoka (snake), Mbiti (hyena), Mbuku (hare), Munyambu (lion), Mbiwa (fox) or domesticated animal names like Ngiti (dog), Ng’ombe (cow), or Nguku (chicken) were given, on unusual circumstances, to children born of mothers who started by giving stillbirths. This was done to wish away the bad omen for the child to survive otherwise it would die like the preceding ones. Sometimes the names were used in order to preserve the good names for later children.

Initiation: Normally, the elders in the community decide when and where the initiation ritual is to take place, but always in consultation with the parents concerned. There is no fixed age when one should be initiated. Before preparation for the circumcision rite could officially start, one initiated man or woman had to volunteer to host the event at his/her home. The preparatory process took 10 days. Three days before the actual physical operation, the parents of the candidates prepared some beer known in Kikamba as “uki was kunoa wenzi” (literally the beer for sharpening the operating knife). The process normally took place during the cool dry weather months between July and October as it was believed that such a climate helps the cut to heal faster.

Soon after the preparation, the period of seclusion (usingi) began. On that day early in the morning the parents bring their boys and girls to the home of the sponsor (mwene nzaiko). Those to be initiated are handed over to the sponsors (avwikii). The candidates are similarly handed over to the circumciser (mwaiki). This handing over symbolizes the entering into a period of seclusion, a period that detaches them from their previous status in society. The first circumcision rite for the Akamba describes and dramatises the passage from childhood and introduces the candidate (musingi) into the community as an adult.

Akamba circumcision or clitoridectomy was performed when the initiates were as young as four or five years. To become a full adult member of the tribe a man or a woman had to undergo two initiation ceremonies – nzaiko ila nini (the small circumcision) and nzaiko ila nene (the great circumcision). The candidates for the second nzaiko were generally eight and twelve years old.

Both boys and girls were taken to a specially erected hut in a thome where they stayed together receiving ritual and practical instructions from instructors. The boys underwent a second operation – a slight cut being made at the base of the glans penis and beer poured into it. There was also a “third initiation” whose participants in the third nzaiko or the “circumcision of the men” were bound by an oath of secrecy. Several researchers speak of the difficulty of getting information on the true nature of the rite. The ceremonies took place far away from the homestead in special huts near rivers and were performed by men who had already undergone the ceremony.

Marriage: During marriage ceremonies dowry is paid in form of goats and cows and recently money. In Kamba culture, before marriage, a man must pay a bride price (known as dowry), in the form of cattle, sheep and goats, to the family of the bride.

Elders and leadership: Elders were responsible for administrative and judicial functions as well as overseeing religious rituals and observances.

The Akamba had institutionalised age-grades which had political and ritual functions. However, the age-grades were not connected with physical circumcision ceremonies as among the Agikuyu. Nzama was and still is formed of atumia (elders) but not all elders took part in its deliberations as there were three categories of elders. The junior-most were the atumia a kisuka who took part in war discussions and were responsible for peace maintenance, carrying out public executions and the disposal of corpses. They paid ten goats or one bullock on entering kisuka eldership.

The top two grades of elders form the nzama, the administrative and judicial council of the larger political unit called utui. The nzama is also known as atumia a nzama or atumia ma ithembo with the inner council known as nzili. This inner council conducts ritual ceremonies. Members of kisuka are allowed to attend rituals but take no part in them.

Death: The Akamba believe in the after-life. They believe that the departed continues to live in another world, which resembles the physical one, although he has more access to the governing force of nature.

Language: Embu or Kiembu. Alternate names: Embu. Embu is the place and tribal name. Language family: Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Southern, Narrow Bantu, Central, E, Kikuyu-Kamba (E.20).

Origins of the community: The Embu are believed to have migrated from the Congo Basin together with their close relatives, the Kikuyu and Meru people. It is believed that they migrated as far as the Kenyan Coast, since the Meru elders refer to Mpwa (Pwani or Coast) as their origin. Conflicts there, perhaps slave trade by Arabs, forced them to retreat north-east and settled by the slopes of Mount Kenya.

Embu mythology claims that the Embu people originated from Mbui Njeru in the interior of Embu, close to Runyenjes town. The mythology claims that God (Ngai) created Mwenendega and gave him a beautiful wife by the famous Mbui Njeru waterfall -hence her name “Ciurunji”. The couple was blessed with wealth, and their descendants populated the rest of Embu.

The Embu and the Mbeere settled in the modern day Embu and Mbeere Districts between the 16th and 17th centuries, having trekked as a unified group from a country in the north of the present Meru District. The country has been speculated to be modern Ethiopia, referred to as Tuku or Uru in oral history. They trekked through Meru and initially settled at Ithanga in Mwea from where they were forced to move due to a great famine that struck the land. After crossing the river Thuci at a place known as Igamba Ng’ombe (literally, where the noise of the cattle is heard), they are said to have separated into two major groups. The Embu settled in the forested slopes of Mt Kenya, while the Mbeere moved further south eventually settling near Kiambere Hill.

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Embu number 324,092. In 1918, the Embu population was 53,000 (24,590 males and 28,410 females), increasing to 85,177 by 1962 and 278,196 in 1999, with a reported annual growth rate of 3%.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Embu settled in Embu District in Kenya, one of the twelve districts in the Eastern Province of Kenya. Embu District is bordered by Mbeere District to the east and south-east, Kirinyaga District to the west, and

Tharaka Nithi District to the north: The main physical feature is Mount Kenya to the north and north-west at 5,200 metres above sea level. The district’s landscape is characterized by highlands ranging in altitude from 1,500 to 4,500 metres and midlands lying at 1,200 to 1,500 metres.

To the west Embu highlands merge with the hot, dry semi-arid southern Mbeere plain over a formerly undemarcated zone of separation with Mbeere, several miles wide. Embu is about 540km² and the main physical feature is Mount Kenya that stands to the north and north-west at an altitude of 5,201metres above sea level. Most of Embu is characterised by ridges and deep valleys except along the Embu-Mbeere border.

Housing: The earliest ancestors of the Embu are believed to have lived in caves and later in villages (matuura)-a dispersed collection of homesteads, which became the basic settlement unit. Settlement was influenced mainly by the availability of water and proximity to farming land, and tribal life was characterized by self-sufficiency. Homesteads were built in circular forms and were hedged.

The shelter was dominated by cylindrical walls and conical hut roofs thatched with grass, banana leaves, ferns, or reeds, with wooden poles used to make the walls. Doors were made of upright sticks woven with creepers or stalks of banana leaves. These huts have been modified, with original circular, cone-roofed, grass-thatched huts giving way to rectangular and corrugated iron-sheet roofing by 1973.

Economic activities: The Embu are cash crop and subsistence farmers who also rear cows, goats and sheep. Embu lies on the windward slopes of Mt. Kenya. The region enjoys two seasons each year and the weather is favourable for diverse agricultural activities. The main foods grown are maize, beans, yams, cassava, millet, sorghum, bananas and arrowroot. This, alongside the domestic livestock of cows, goats, sheep and chicken. The main cash crops introduced in the area with the advent of colonialism are coffee, tea, and macadamia nuts.

Originally, the Embu and the Mbeere were hunter-gatherers, thereby dependent on meat from wild animals, wild fruits and edible tubers. They later developed a pastoral culture, probably influenced by the Maasai they encountered. They adopted agriculture, grew tubers such as yams, sweet potatoes and cassava; grains such as millet, sorghum and pigeon peas. Though the Mbeere practised some farming, scanty rainfall and soil infertility made them concentrate more on rearing livestock, especially goats.

The main subsistence food crops are maize, beans, potatoes, bananas, yams, sorghum, millet, cow peas, pigeon peas, and cassava. The staple food is a mixture of maize and beans, kithere. Other crops grown include fruits such as mangoes, oranges, pineapples, passion fruit, pawpaw; horticultural crops such as onions, tomatoes, carrots, French beans, cabbages and kale.

Animals kept include hybrid cattle, poultry, pigs and sheep.

Trade: The Embu traded with the Kamba and Waswahili whereby they exchanged grain and animal skins for honey, arrows and poison with the Kamba, and gave the Waswahili slaves in return for spices and ornaments.

Cycles of life The clan constituted the most basic kinship unit at the community level, with patrilineal descent as the basis of clan membership.

Education: Informal education, training and other traditional social institutions were used for value transmission of societal expectations for male and female youths. Children were educated mainly in the family, with emphasis placed on values such as team spirit, honesty, obedience, courage, and respect. After infancy the father took charge of boys’ education and the mother educated the girls.

Initiation: Every group of initiates was given a name -the name depicted the current situation in the community for example if a group of children was circumcised during an exceptionally heavy rains that caused flooding, or during an outbreak of an epidemic such as smallpox, the age group was given a name that described the particular situation.

Marriage: Traditionally, parents arranged marriages, usually with the consent of the marriage partners. Bride-wealth was fixed at four cows and a bull, plus six to eight goats, paid after completion of the negotiations. Poor men who could not afford to pay at least a portion of the required amount were allowed to marry and were temporarily adopted by the father of the bride. Then couple then worked to raise the payment to win their independence.

Death: The Embu traditionally believed that the dead continue to inhabit the world of the spirits and did not bury their deceased persons until the 1920s, when the British government and Western churches made burial mandatory.

When a person became very sick and beyond saving, a shelter would be built in the bush and relatives would stay with that person. After death the corpse was left unattended to be eaten by hyenas as the relatives went home to engage in a cleansing ritual. The deceased’s hut was then set on fire. When a man died, a cleansing ceremony was performed on the widow, who later was inherited by one of his relatives. A woman’s death was followed by little ceremony because she had no home of her own. If an unmarried man died, his place of death would not be cultivated.

Language: Kitharaka. Alternate names: Saraka, Sharoka, Tharaka. Tharaka is the place name. Atharaka is the name of the group.

Language family: Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Southern, Narrow Bantu, Central, E, Kikuyu-Kamba (E.20), Meru. Origins of the community

Population: According to the 2009 Kenya population and households census results the Tharaka number 175,905 up from 139,000 in 2006.

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Tharaka settled in Eastern Province’s East Meru district, Embu district; some in Kitui district. Some Tharaka people live outside their homeland. Housing

Economic activities: The Tharaka are farmers, keeping cattle, goats and sheep and growing cereal crops, cotton and sunflowers.

The Tharaka are farmers but also rely a lot on pastoralism; the rearing of cattle, goats, sheep and also poultry.

In the upper zones of rain fed cropping and mixed farming livelihood zones, crops such as drought tolerant varieties of maize, pigeon peas, beans, cow peas, millet, sorghum and green grams are cultivated. Livestock kept include cattle (local and cross-breeds), goats (both meat and daily), sheep, poultry, bees and donkeys. Trade

Cycles of life Marriage: Marriage brings the woman’s family in close relation with the man’s and involves the payment of bride price to the bride’s father by the groom’s father. The marriage ceremony itself is marked by a lot of celebration and beer drinking.

The Mwimbi-Muthambi are closely related to Meru, Chuka, and Tharaka peoples.

Language family: Niger-Congo, Atlantic-Congo, Volta-Congo, Benue-Congo, Bantoid, Southern, Narrow Bantu, Central, E, Kikuyu-Kamba (E.20), Meru. Origins of the community

Geographical location of the community: After their last migration, the Mwimbi-Muthambi settled in Eastern Province’s Central Meru district.